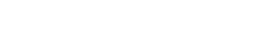

Four-time world boxing champ Abner Mares explains his life’s trajectory — escaping poverty and violence to rise to the top of three weight classes — with the simple statement: “I just don’t give up.”

Mares has triumphed with the motto: “Losers fail because of the circumstances, and winners win despite the circumstances.” This attitude helped Mares survive the streets of a Southern California neighborhood that was a virtual war zone in the 1990s, when he first arrived in the U.S. at 7 years old. At the time, the FBI estimated one in 15 Hawaiian Gardens, Calif., residents had a gang affiliation. Mares shared a one-bedroom apartment with eight siblings and his mother, who worked three jobs and struggled to make ends meet. Mares says hunger was a constant presence, and he recalls dumpster diving for discarded food.

The Mares home was in contested gang territory, and gun battles plagued the neighborhood. Mares’s fighting abilities helped him survive, and gained him respect, but they also drew him closer to gang life.

“I’m not gonna lie,” he says now. “It helped me, the street rep. I was a good fighter. They had respect for me because I would always beat up the older guys. They wanted to jump me into the hood.”

His family had other ideas. When his father (who by this time had joined the family in America) learned Mares was about to be initiated into the local gang, he sent his son back to relatives in Guadalajara, Mexico. It was a harsh transition for the 15-year-old, but the move led Mares to land a spot on the Mexican national boxing team. Word of his abilities had preceded him. He recalls, “They had me spar their number one guy. I beat him up.” Four years later, he was boxing in the Olympics for Mexico.

As an amateur, Mares racked an impressive record of 112-8 wins with 84 knock outs. But when he went up against Hungarian Zsolt Bedák, he lost in a controversial 27-24 decision.

“I didn’t lose,” Mares insists. “I was robbed.”

World-renowned boxing coach Luis Garcia still remembers the first time he saw Mares fight. He knew immediately the young boxer was a champion. It didn’t matter that Mares hadn’t medaled at the Olympics — Garcia recognized talent when he saw it. He’s now Mares’s strength and conditioning coach.

When the two first met, Garcia was working for Mexican-American boxing legend Oscar de la Hoya training a stable of boxers signed to the former champion’s club, Golden Boy Promotions. Garcia saw Mares sparring at local gyms and knew he was in the presence of someone special. He could see the younger man’s focus and work ethic. As Mares says now, “I worked for my talent.”

Garcia also has a mantra. “Having a heartbeat doesn’t mean you’re living. That’s called existing.” He saw that Mares was willing to put in the hours necessary to become a champion. Garcia quickly shared his discovery with De la Hoya. “I told Oscar right away: ‘That kid right there is pretty much the heir to the throne.’” De la Hoya signed Mares immediately.

The then-19-year-old immigrated back to the U.S. with his wife to join Golden Boy and train with Garcia. Mares’s first professional fight was against Luis Malave. Mares sent him packing in the second round with a technical knockout. A string of successes followed, until he took a blow to the face that sent him reeling. A doctor told him, “You can’t fight anymore. You’re done.”

A detached retina felled him. A boxer can’t fight if he can’t see. Worse still, there were long-term implications to consider — the potential for diminished sight, perhaps even permanent blindness.

Mares now had a family to feed. He reluctantly hung up his gloves and took any job he could, even working as a security guard at a local high school. But he never stopped missing the ring. Nearly two years after that career-ending diagnosis, his wife urged him to get a second opinion. The new doctor declared neither the boxer’s sight nor his career was at risk.

Mares isn’t bitter about the time he lost, however. For him, the two years away proved a learning experience. “That’s why I work so hard, because everything or anything can be taken away from you just like that, like the snap of your fingers.”

Four championships later, Mares is still fighting strong. But he says his family remains the main focus of his life, and he doesn’t like being away for long. “I need to get home to those smiles,” he explains. “I need to have that love.”

No longer a teen sensation, Mares now trains harder and wiser. He throws fewer punches, but lands more. He’s happy to have matured. “I love it now!” he says. “I’m excited to be fighting at this age.”

As we go to press, Garcia is training Mares hard for his long-awaited rematch with Leo Santa Cruz, who bested Mares in a 2015 title fight (the year the documentary Getting to Know: Abner Mares was filmed). Mares says he just wants “redemption.” He and Garcia have had three years to develop a different game plan. They’re not worried about the outcome.

Regardless of who is declared the winner, Mares and Garcia will both go home to families that love and sustain them. With that kind of support behind them, the boxer and his coach can’t lose.

READER COMMENTS (